The Women’s Courtyard, by Khadija Mastur, translated into English from Urdu, by Daisy Rockwell, begins with the protagonist, Aliya, having a sleepless night at her Uncle’s place, recalling and pondering on how her life will be from now onwards. In the next few chapters, she recalls how she as a child, had shifted to a newer place that was bereft of any life, community or togetherness and how her previous home was filled with love, friends, and endless entertaining stories that her Khansaman Bua used to regale her with.

The book then jumps into the present and narrative speaks of the events that lead up to that point where Aliya is now restless and pondering over an uncertain future in her Uncle’s house.

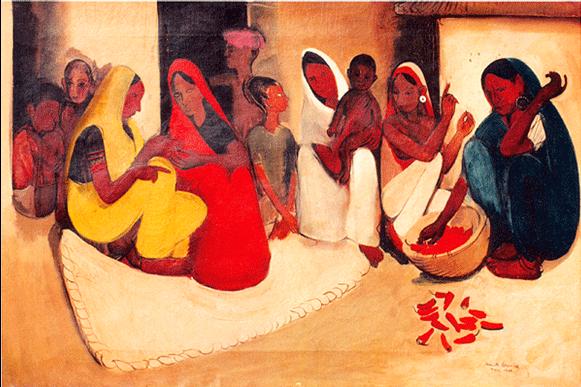

Titled, Aangan, in the original Urdu, the novel is set in pre-Independence India (somewhere in North India) and narrates how the Independence movement affects the men and women of the house. It is the women who are the main characters and the house or the courtyard (angan in Hindi/Urdu) is their stage.

The story is told from the perspective of Aliya, focusing also on other female members of the house such as Aliya’s mother, her elder sister, Tehmina, her friend Chammi and Kusum. The Independence movement takes place in the background for the women yet the male members’ intense involvement and particularly the rivalry of Jameel (Aliya’s cousin) and her Uncle rip the household. Jameel supports the Muslim League whereas his own father is a staunch Congress supporter. Their bitter rivalry tears them apart so much so that they do not speak to each other. Aliya’s own father’s involvement in the movement is what forces her and her mother to shift into her Uncle’s house which is where the novel begins. (caution: one cannot simply base their assumptions about the Independence movement through a reading of this novel and dismiss the contribution of women to the movement).

The Women’s Courtyard does proffer a varying perspective on how deeply it affected women of the time and how it makes them adjust and compromise on every level as well. The novel is not a critique of the movement but rather of the patriarchy that is embedded in society and even in the movement. While it is important to fight for one’s country which the men in the Aliya’s family do, they themselves are caught between their roles of being breadwinners and freedom fighters which shows the pressures that they themselves faced from their family and society. On the other hand, the stage of the house in the novel and the Aangan makes the reader view a traditionally female occupied space and how their world is confined to that. While the men are out there fighting for freedom and having discussions about that in the drawing rooms, the women are never privy to that world. The female gaze does not trespass that territory even though it affects them in various other ways such as emotional and financial. Aliya is the only one who is shown reading and learning about the movement from her Uncle and his encouragement to read his books. The novel portrays several gender expectations imposed at that time which are applicable even today where women are not allowed to be part of certain decision making processes in several areas and cultures of the subcontinent.

Through her college, her reading and her exposure to her immediate world, Aliya, is the diplomatic yet empathetic voice in the story who is able to recognize the unfairness in the way in which society treats people, especially women. Her understanding and ability to interpret and reason make her absolutely logical with a touch of empathy for everyone around her. For example, her notions around love and marriage is shaped by how her friend, Kusum, was treated unfairly by gossip mongers for eloping and how Tehmina lost her senses because of falling in love. She is cautious herself about falling in love and stays away from something that she considers quite irrational. It is not merely the idea of love she detests but the manner in which it is ingrained into women. Thus she severely critiques this wrong notion of how women are expected to behave when in love which is quite relevant even today.

The Women’s Courtyard, is a thoroughly engaging read that unsparingly critiques all facets of patriarchy from Aliya’s mother’s entrenched beliefs regarding women and need for punishment for transgressive women or her aunt’s own pride in her Master’s degree and her condescending attitude toward one and all. It is a beautifully translated novel that captures the tense atmosphere both at Aliya’s home and outside. The one aspect that would have added to the novel’s charm would have been to include certain phrases and lines in the original Urdu, even if romanized.