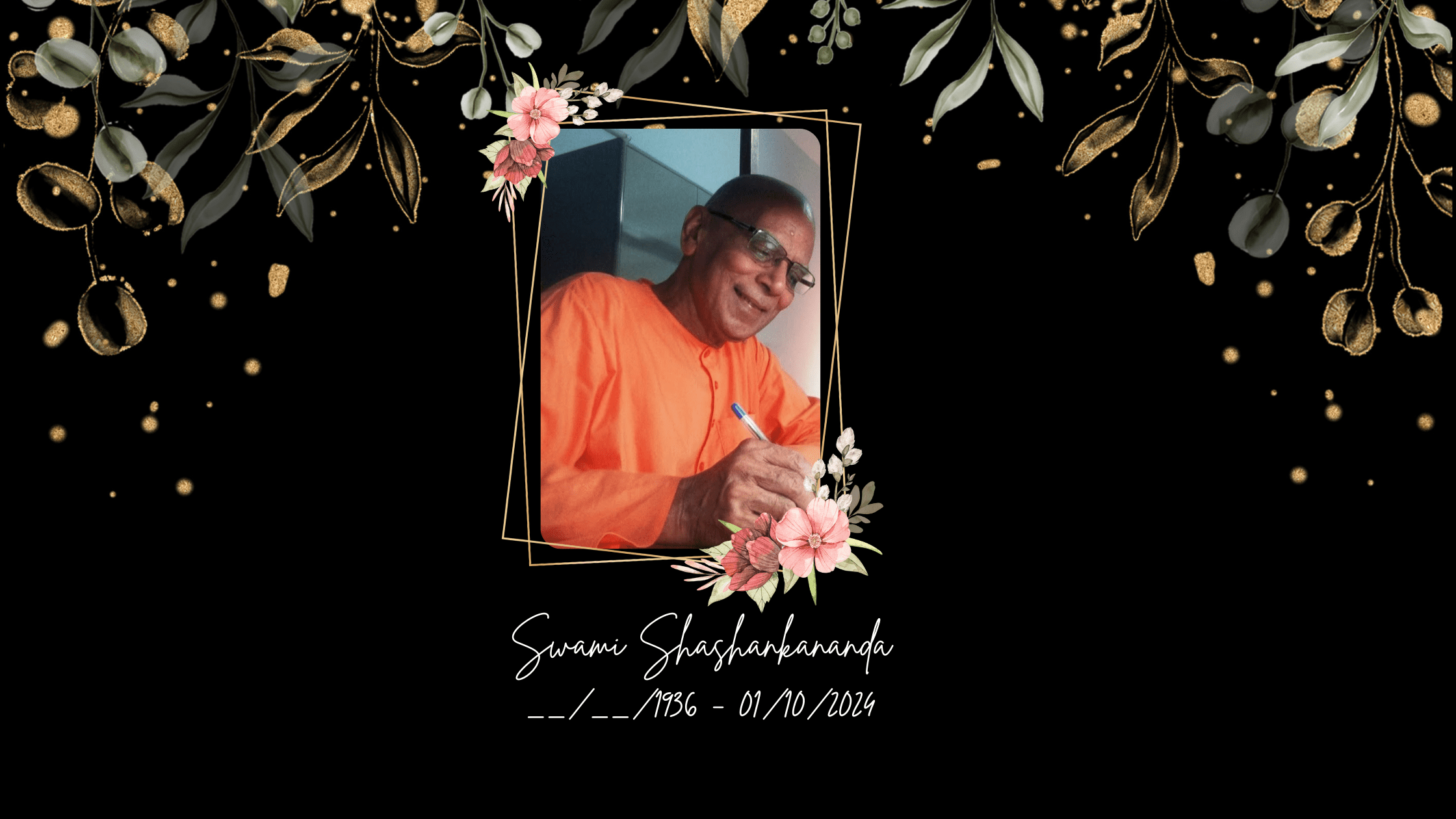

It is with deep sorrow and anguish that we inform you that on 1st October 2024 at 11:43 am, most revered Swami Shashankananda Ji Maharaj left his mortal coil at Ramakrishna Mission TB Sanatorium Hospital, Tupudana. We were fortunate to have his august presence at our Morabadi ashram on 30th September for the Temple shifting ceremony. Maharaj Ji dedicated his life to spread the message of Thakur, Maa and Swami ji. Let us take a moment to pay our homage at his lotus feet.

Swami Shashankananda Ji Maharaj joined the Ramakrishna order as a Brahmachari in 1963 when he was initiated by most revered Swami Madhavananda Ji, the then President of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. Later he received his Sanyas Diksha from Swami Vireshwarananda Ji Maharaj. He served at the Headquarters (Relief Office) and at various places through out India like Delhi, Chandigarh, Khetri, Raipur, Narottamnagar, Taki and Saradapeeth as an assistant.

He had a special attachment with Swami Atulananda Ji maharaj, whom he served as an attendant in the former’s later days. At Delhi Ashram, he was inspired and guided by Swami Ranganathananda Ji and Swami Swahananda Ji. He was given the herculean task to start an integrated rural development project under the name ‘Pallimangal’ by Revered Swami Vireswarananda Ji Maharaj and Swami Atmasthananda Ji Maharaj.

He played a leading role in establishing Pallimangal activities at Kamarpukur and neighbouring villages and also in the construction of 100 houses at Baptalla of Guntur district in Andhra Pradesh. Workers, volunteers and villagers of Kamarpukur, Jayarambati and neighbouring villages still remember him fondly for his contribution in the fields of agriculture and cottage industries like manufacturing of incense sticks, weaving, bakery, bee-keeping etc. He served as the Principal of Samaj Sevak Shiksha Mandir at Belur Math and set up many subsidiary organisations for youth and marginalised sections of Bengal especially around Sundarban area.

Just as Swami Swahananda had once prophesied that “Mahesh (Swami Shashankananda) will serve the Indian villages”, Maharaj Ji was posted at RKM Morabadi, Ranchi in 1997 to serve the tribal villages around the area. He was further inspired by a phone call by Swami Ranganathananda Ji maharaj encouraging him to carry the message of the Bhagavad Gita to the villages. Swami Ranganathananda Ji also motivated him to work towards the abolition of Casteism and Untouchability.

He had composed Chowpais and Dohas on the life and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna which were full of dedication and devotion towards the holy trio and were loved by both lay devotees and monks alike.

Swami Shashankananda was not only a firm believer in the life and teachings of Swami Vivekananda but worked towards realising them in the fields of agriculture, rural development, tribal education and others.

He had a dauntless and indomitable personality and never compromised on his sense of morality and vivek. He believed that in a state like Jharkhand which is full of natural resources viz. land, water, wind etc, the solution to all higher education woes would be to teach students the knowledge to harness these renewable natural resources in a holistic manner. In 2013, he was invited by the then Chief Minister of Gujarat Shri Narendra Modi Ji as a Chief Guest for a state rural and agricultural programme. In his introductory speech, Modi Ji spoke at length about the dedication and ability of Swami Shashankananda Ji Maharaj.

His suggestions regarding the same were taken up sincerely by the State Governments as well as the central Government. Recently, by his relentless pursuit and sincerity, he was successful in introducing integrated Agriculture Education courses in the Government Schools of Jharkhand. He had been engaged in rural developmental activities for 55 years including 18 years in West Bengal and Orissa and 27 years in Jharkhand. He served as the President of Bihar-Jharkhand Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Bhava Prachar Parishad for 17 years and had a tremendous role to play in doubling the membership of Private Ashramas from 15 to above 30. He was the founder Head of Ramakrishna Math, Purnia. For the last 5 years, he had set up his base in Mamarkudar (Bokaro, Jharkhand) and was working for the emancipation of poor children around the area by imparting them with scientific education coupled with spirituality and the ideals of Swami Vivekananda in a formal setting.

He was a multi-talented personality and was a composer, writer and singer. Maharaj Ji was not only a learned scholar but he was an author of numerous books as well as an orator par excellence. He also had a deep understanding of Homeopathy medicine. His melodious voice when he used to sing bhajans used to enthral one and all. When he used to sing ‘Sri Ramakrishna Katha Sarovar’ everyone listened with rapt attention and devotees used to get immersed seamlessly in the bhava of Thakur (Sri Ramakrishna).

He dedicated his life to spread the message of Jiva Seva Shiv Seva (service to mankind is service to God) from village to village and city to city. Maharaj Ji was an embodiment of all that is good and noble. He is an inspiration to all of us present here. Let us all pay our respects to him today and remember the Shloka from Shrimad Bhaagvat which he realised by his life’s work.

न त्वहं कामये राज्यं न स्वर्गं नापुनर्भवम् ।

कामये दुःख तप्तानां प्राणिनामार्तिनाशनम् ॥

O Lord! I do not desire a kingdom, I do not want the bliss of heaven, and I do not even desire salvation. My only desire is that the suffering of beings tormented by sorrow should end.

Om Shanti!

As written and read by Sri Suresh Narayan Jha during the condolence meeting by the governing body of Ramakrishna Mission, Morabadi (Ranchi) and published on the ashrama’s website. TheSeer stands together in grief with all the devotees and lives impacted by Swamiji’s life, work, and eventually his passing away.